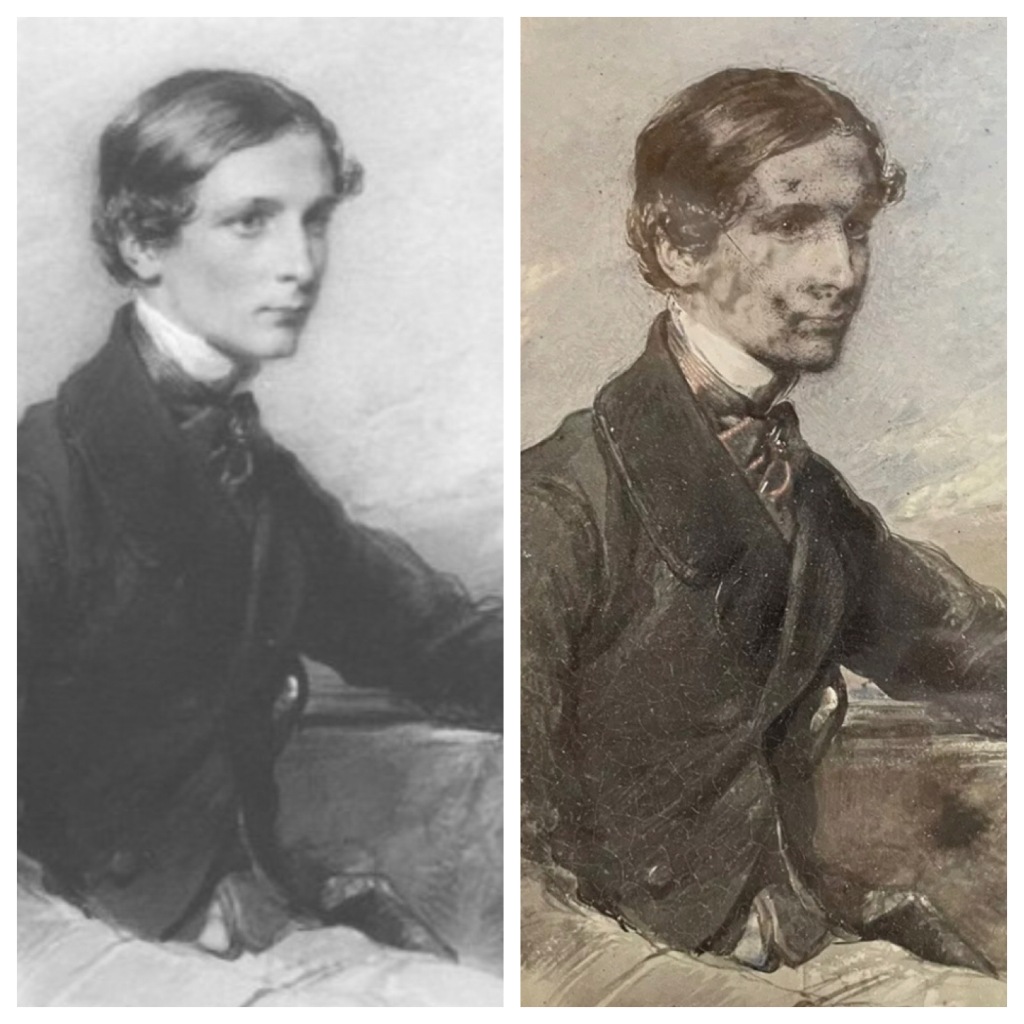

This is a portrait of a young woman in watercolour with some body colour, painted on paper and measuring 345 x 450mm. It is inscribed in the bottom left corner: ‘Geo. Richmond, delt, 1852”.

I have no reason to doubt this is anything but a genuine Richmond portrait, it is characteristic of his work, the signature is correct, and the picture was untouched in its original James Henry Chance frame.

Assuming the artist and date are therefore correct, who is the sitter?

I’ve been considering a couple of theories. What follows are my research notes and some early speculation.

The “Shelley” Conjecture

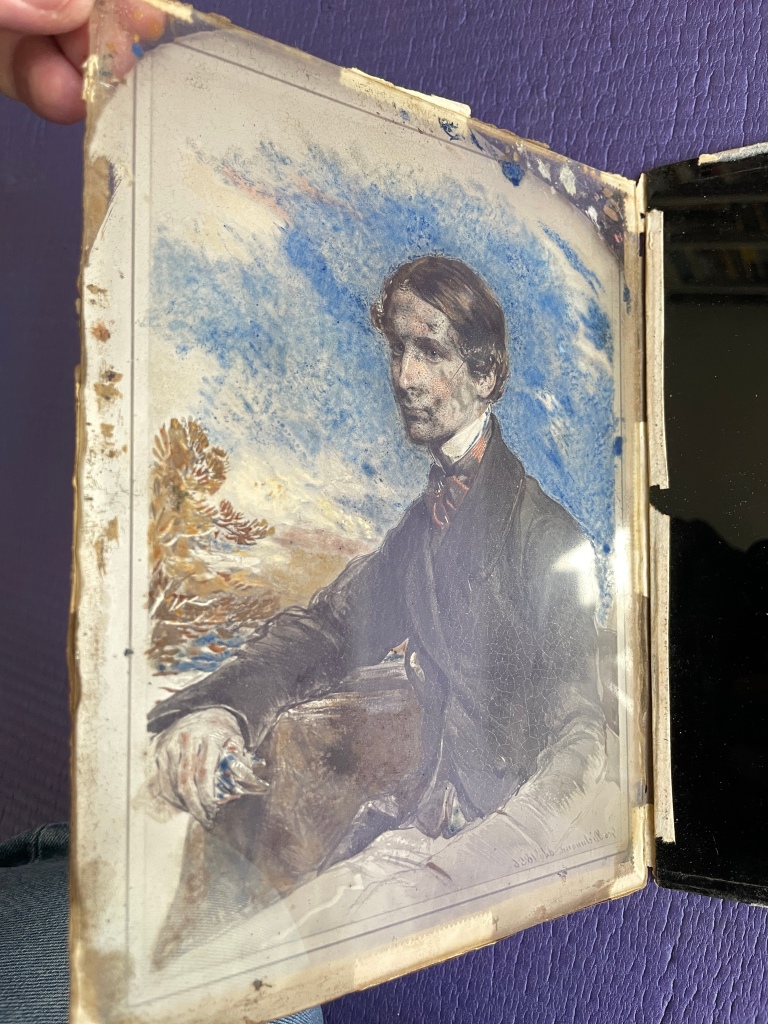

The first potential clue to the identity of the sitter is on the back of the picture, on the top of the frame, where written in a modern hand, is “Miss Shelley (?)” and “3”. There is also a printed label that reads “SHELLEY 1882”.

The question mark of course suggests the attribution as Miss Shelley is a guess, an identification perhaps prompted by the label, which may have nothing to do with the Shelley family name. Despite some extensive searching the label remains a mystery. It is also unclear what the label represents and whether the reference to 1882 is a date or an unconnected number.

So, is there anything else would make anyone suggest the sitter is Miss Shelley? The answer could come from the 1852 date. By 1852 Richmond had been a prolific portraitist for decades but if we look at the known, but not necessarily complete, record of his portraits from 1852 (they come from information in his diaries and account books), and exclude portraits of men, then we end up with a list of some 30 pictures. On that list is the following entry:

Shelley. Miss (Aunt of the Poet) £42 1852

It is possible someone has simply seen the 1852 date and asked if this could be Miss Shelley. Is there anything else therefore to connect or help identify Miss Shelley as the sitter, other than a date and a seemingly random pick?

There is another known connection between the Richmond family and the Shelley family. Richmond’s mother, Mrs Thomas Richmond née Anne Oram (1772-1859) knew the poet Shelley when he had lodged in the same house as her in Half Moon Street, Piccadilly. That does seem to be a rather tenuous connection.

The known price for the work may be relevant – the majority of Richmond’s portraits are likely to be mid-sized watercolours or chalk drawings. It looks like Richmond’s standard charge in 1852 for that format is £31.10. But the portrait of Miss Shelley is more expensive at £42. It is possible the portrait of Miss Shelley is a larger format work but this is not borne out by our picture. The increased price can however also cover the production of a companion portrait. I have, for example, a pair of portraits of Mr and Mrs Penrhyn of similar size and from just a year later where the price charged for the pair is £42. The increased price can also include the cost of having the picture engraved but there is no evidence this one was.

All of this speculation may however be academic as we now come to the major, and potentially fatal problem with the Shelley identification. Our sitter is, generally speaking, a young woman. The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) famously died young, at 30 years of age, but his death was 30 years before this painting. His aunt (on his father’s side, to have the Shelley name) is not going to be a young woman. The poet’s father Sir Timothy Shelley was born in 1731 and had died in 1815. He had three sisters: an older sister Helen who was born before 1731 and must have been long dead by 1852, and two younger sisters Ariana and Jane Caroline Shelley, but both of those seem to have been born before 1771 so would be at least 80 years of age in 1852. The spouses of Shelley’s uncles also don’t match our sitter.

Either the description in the account books of Miss Shelley as “the poet’s aunt” is wrong (which seems unlikely) or the sitter can’t be Miss Shelley. Of course the best evidence to discount this as being Miss Shelley would be to find the actual portrait of Miss Shelley, which so far I’ve been unable to do.

The Lascelles Theory

I haven’t given you the full story about the back of the picture. There is another possible lead to consider. On the wooden backing board, in pencil and in a different hand, is written the phrase “for Giles Lascelles”.

Now it may just be a coincidence that someone called Lascelles is mentioned on the back of this picture and they may have no connection with the sitter. The Lascelles name however is of huge interest because a) it is not a common British name b) it is associated with the aristocratic Lascelles family, one branch of which is headed by the Earls of Harewood and c) it generates a least one well documented connection I already know about with George Richmond. All of these may help identify the sitter.

I have two reference points to work from – the modern reference to “Giles Lascelles” and the 1852 date of creation. Is it possible to connect these two references, to either identify the sitter, or develop a provenance?

I’m starting with the 1852 date as it relates directly to the painting. Going back to the list I created of Richmond’s 1852 female portraits we find this entry:

Miss Lascelles £31.10 1852

Again, this is possibly a coincidence but maybe there is a Lascelles connection. So, who could “Miss Lascelles” be and would she match this image?

We have visual clues from the painting. If this is Miss Lascelles, she has to be a young woman of around 18 to early 30s in age (although estimating the age of sitters in portraits of this time is difficult). She has to be unmarried (to be “Miss” Lascelles) which might be supported by the visual clues as to dress, the lack of a wedding ring etc. We also have to consider whether there is a reason for commissioning a portrait e.g. to commemorate a marriage or engagement.

There is one other visual clue, in that the sitter appears to be wearing mourning clothes, particularly black bracelets – so a close relative is likely to have died recently, but not too recently, as she is not in full mourning dress.

I’m now looking at any female members of the Lascelles family to see who might fit those criteria. One of the benefits of aristocratic families is that their lineage is well documented even if, in the traditional way, the family tree is confusing as they repeatedly adopt the same limited repertoire of names.

Let’s start at the top. In 1852, the head of the family was the third Earl, Henry Lascelles (1797-1857). Not much to say about him except to note he is still alive in 1852, so he is not being mourned by his family. The third Earl married Lady Louisa Thynne(1801-1859). This is the Lascelles connection to Richmond that I already knew about because Louisa, Countess of Harewood was painted in a full-length oil by Richmond in 1855. The painting appears on the cover of Raymond Lister’s biography of Richmond and is still in the Lascelles family seat, Harewood Hall near Leeds. So we know that Richmond was familiar with the Lascelles family and painted the countess three years after our portrait.

Could Miss Lascelles be a daughter of the Earl and Countess? They had 13 children including 6 girls, although the later children would be too young to be the subject of our painting.

The eldest daughter is Lady Louisa Isabella Lascelles (1830-1918) who would be 22 years of age in 1852. She marries Charles Mills, 1st Baron Hillingdon in 1853 so is still “Miss” Lascelles and it is possible that this could this be an engagement picture. There is photograph of Louisa Isabella taken in the 1860s where she looks remarkably like her mother but not at all like our portrait.

The next daughter is Lady Susan Charlotte Lascelles (1834-1927) who would be 18 in 1852. She married Edward Montagu-Stuart-Wortley-Mackenzie, 1st Earl Wharncliffe in 1855 so is still Miss Lascelles, but at 18 she seems to be to be at the very edge of the viable age range for our picture. There is a photograph of her in 1874 and a watercolour portrait by xxx in 1888 which although decades after the painting don’t suggest a particular resemblance.

The other four daughters: Lady Blanche Emma Lascelles (1837-1863); Lady Florence Harriet Lascelles (1838-1901); Lady Mary Elizabeth Lascelles (1843-1866) and Lady Maud Caroline Lascelles (1846-1938) would be too young, at 15, 14, 9 and 6 respectively in 1852, to be our sitter.

Finally, there is a rather magnificent, privately printed, catalogue of the art at Harewood House produced by the art historian Tancred Borenius in 1936. Whilst that lists a series of Lascelles portraits including Richmond’s portrait of the Countess Louisa it does not mention any other portraits of her daughters. This is actually reassuring, if it had been the Harewood Lascelles I imagine it would still be in the house today.

So, whilst Lady Louisa and Lady Susan could still be our sitter the lack of resemblance to the (admittedly later) photographs is a concern, and the fact there is no record of a portrait at Harewood as I’d expect, and there is no obvious relative they are likely to be mourning tends in my mind to rule them out as contenders.

We should however consider the other branches of the Lascelles family and that takes me to the children of William Saunders Sebright Lascelles (1798-1851) the brother of the 3rd Earl. He had 5 daughters of 10 children with his wife Caroline Georgiana Howard (?-1881) (she is from the Howard/Cavendish family). William was painted by John Jackson in a portrait currently in Hardwick Hall and there is an engraving of a rather striking portrait of Caroline.

Their oldest daughter is Georgiana Caroline Lascelles (1826-1911) who married Charles William Grenfell on 20 Jul 1852. This could therefore be marriage picture and Georgiana would still be Miss Lascelles in the first half 1852. Georgiana was born on 5 January 1826 in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire so would be 26 in 1852 which puts her in the right age bracket. She would also be at the end of a period of mourning for father who died in July 1851. Georgiana would go on to have 1 child, Baron William Henry Grenfell born in 1855. She died on 2 February 1911 at 85 years of age. The 1881 Census records a Georgiana C Grenfell in the house of Robert H Meade (her son in law), at St George Hanover Square, London. We have a portrait of her as a young girl that was engraved later, which although shows a much younger girl does suggest some similarities with the sitter. All of these things, age, mourning, possible wedding portrait make her a good, probably my best candidate for being “Miss Lascelles”.

The next oldest daughter is Henrietta Frances Lascelles (1830-1884). However, she had married William Cavendish, 2nd Baron Chesham in 1849 so wouldn’t be “Miss Lascelles” in 1852. She had child and would be 22 in 1852. She may be the Mrs Cavendish mentioned in Richmond diary entry (see footnote 1).

The others daughters: Mary Louise Lascelles (1835-1917) Emma Elizabeth Lascelles (1838-1920) and Beatrice Blanche Lascelles (1844-1915) at 17, 14 and 8 years of age respectively in 1852 are too young to be our sitter.

For completeness, the other brother of the 3rd Earl, was Arthur Lascelles but his children are too young (aged 11) in 1852 to be our sitter.

I have therefore two main contenders Lady Louisa Isabella Lascelles (1830-1918) daughter of the third Earl whom I still have doubts about, and her cousin Georgiana Caroline Lascelles (1826-1911) who seems the strongest possibility.

I should also mention that Richmond’s records show a “Mr Lascelles” was painted in 1835 (for £5.5). I can find no trace of that picture and without any hint as to the age of Mr Lascelles it is impossible to identify him.

“For Giles Lascelles”

This phrase is scribbled in a modern hand on the backboard of the picture. Given that, I don’t think this can mean the painting was done for a Giles Lascelles. I’ve also seen notes like this on the back of pictures refer reframing work done for the named client. The frame is however almost certainly the original from 1852 and matches those of other Richmond pictures of that year and around that time. It could of course also mean it was remounted, reserved or sold to a Giles Lascelles in recent years.

So who could Giles be? The most obvious contender is Henry Giles Francis Lascelles (1931-1998) who, according to Burke’s Peerage, usually went by his middle name Giles. He however has a son, also called Hugo Giles Lascelles (b.1958).

Not surprisingly both “Giles” are related to all the other Lascelles. They are however also directly related to Georgiana.

And that is where my current research runs out of steam. I don’t have any provenance to work back from – I bought this picture in a private sale from someone who had no knowledge of the subject. I also can’t find any auction records for the painting – although this is difficult when you have no named sitter to go by. That said, I also can’t find a record for another picture by Richmond of Miss Lascelles which would rule that option out.

So, is this Georgiana Caroline Lascelles? If so, where has it been for 170 years?

Any ideas – let me know.